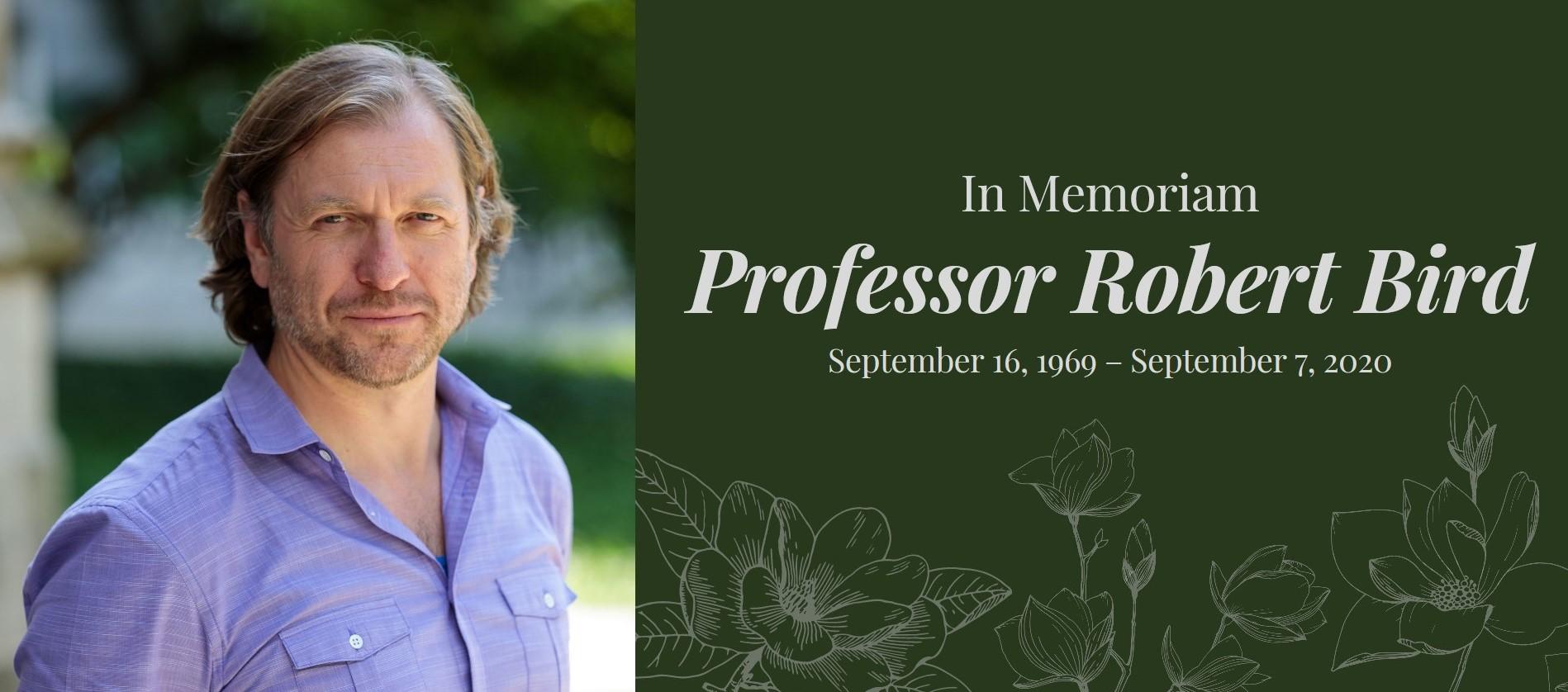

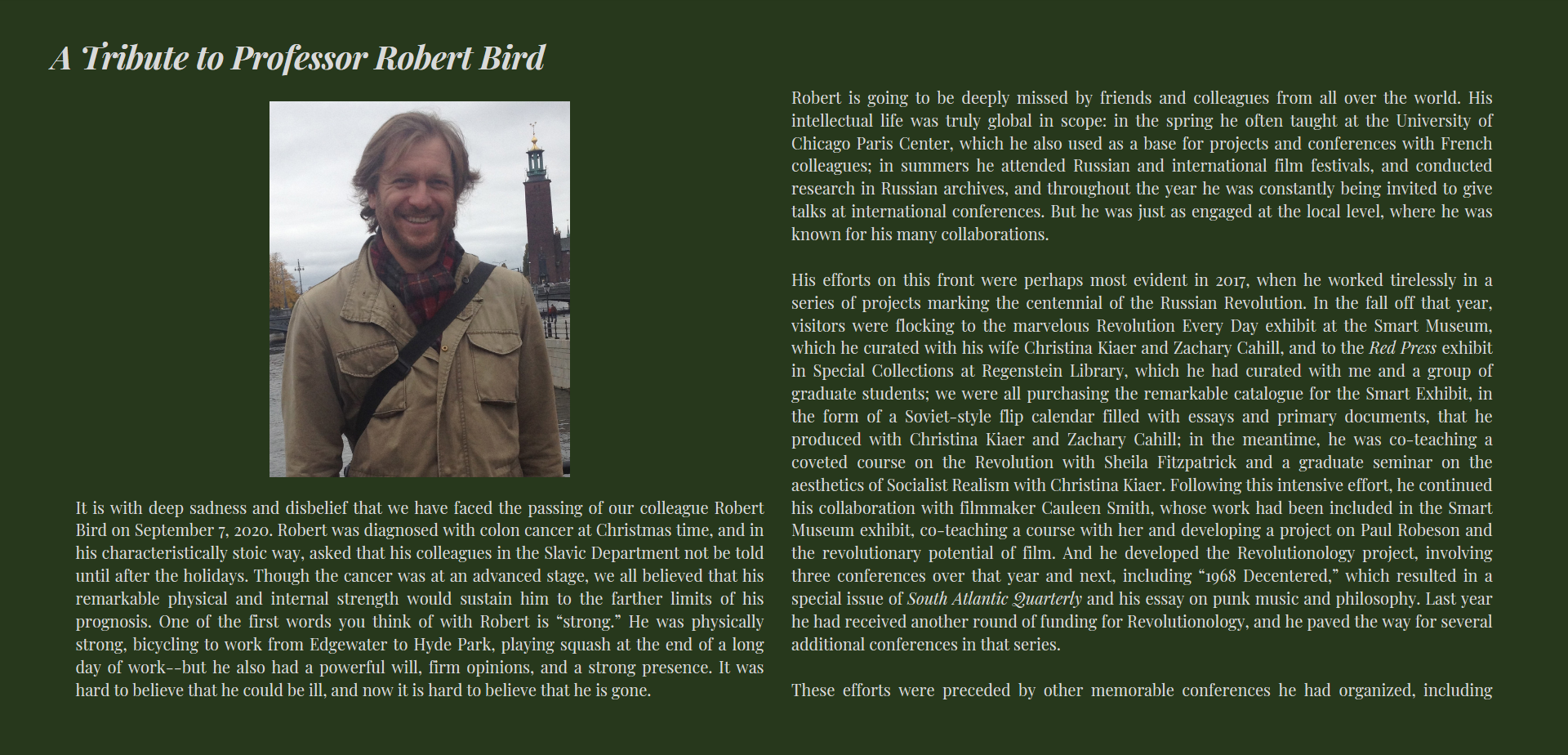

It is with deep sadness and disbelief that we face the passing of our colleague Robert Bird, who died Monday, September 7, after a long illness. Robert was diagnosed with colon cancer at Christmas time, and in his characteristically stoic way, asked that his colleagues in the Slavic Department not be told until after the holidays. Though the cancer was at an advanced stage, we all believed that his remarkable physical and internal strength would sustain him to the farther limits of his prognosis. One of the first words you think of with Robert is “strong.” He was physically strong, bicycling to work from Edgewater to Hyde Park, playing squash at the end of a long day of work–but he also had a powerful will, firm opinions, and a strong presence. It was hard to believe that he could be ill, and now it is hard to believe that he is gone.

Robert is going to be deeply missed by friends and colleagues from all over the world. His intellectual life was truly global in scope: in the spring he often taught at the University of Chicago Paris Center, which he also used as a base for projects and conferences with French colleagues; in summers he attended Russian and international film festivals, and conducted research in the Russian State Film and Photo Archive, and throughout the year he was constantly being invited to give talks at international conferences. But he was just as engaged at the local level, where he was known for his many collaborations. His efforts on this front were perhaps most evident in 2017, when he worked tirelessly in a series of projects marking the centennial of the Russian Revolution. In the fall of that year, visitors were flocking to the marvelous Revolution Every Day exhibit at the Smart Museum, which he curated with his wife Christina Kiaer and Zachary Cahill, and to the Red Press exhibit in Special Collections at Regenstein Library, which he had curated with me and a group of graduate students; we were all purchasing the remarkable catalogue for the Smart Exhibit, in the form of a Soviet-style flip calendar filled with essays and primary documents, that he produced with Christina Kiaer and Zachary Cahill; in the meantime, he was co-teaching a coveted course on the Revolution with Sheila Fitzpatrick and a graduate seminar on the aesthetics of Socialist Realism with Christina Kiaer. Following this intensive effort, he continued his collaboration with filmmaker Cauleen Smith, whose work had been included in the Smart Museum exhibit, co-teaching a course with her and developing a project on Paul Robeson and the revolutionary potential of film. And he developed the Revolutionology project, involving three conferences over that year and next, including “1968 Decentered,” which resulted in a special issue of South Atlantic Quarterly and his essay on punk music and philosophy. Last year he had received another round of funding for Revolutionology, and he was planning several additional conferences in that series.

These efforts were preceded by other memorable conferences he had organized, including “Scale Models: An Interdisciplinary Symposium” (2012), and “In the Long Shadow of Empire: Modern Constructions of Central Eurasia” (2016), which he organized with two graduate students. We were all the beneficiaries of his ambition and his generous commitments. He worked tirelessly with his students, both graduate and undergraduate, and could often be seen holding long sessions with them as he led them through independent studies and research projects. His letters of recommendation were written with painstaking dedication, and were full of the sort of salient details that one can only produce after sustained and close attention to a student’s work. He followed and supported his former students with unbending fortitude, always giving them straight talk on their work and encouragement in their efforts to build their careers. And the same could be said for his colleagues: I personally will always be grateful to him for the extraordinary attention he devoted to my tenure case, and am going to miss his sound advice on topics both professional and personal.

The University community is going to feel his loss whenever a Russian film is shown at the Film Center, where he time and again gave audiences a compelling framework for interpreting and enjoying obscure and classic works of Russian and Soviet cinema. We will miss his sense of humor—always wry, sometimes slipping past unnoticed if you weren’t paying attention. Years ago, a graduate student told me that hearing him read French poetry in a morning class was the highlight of their day. So many of us wanted more time with him, but we can be grateful for the time we had with him, when he gave us so much.

Robert was born on September 16, 1969. He earned his B. A. from the University of Washington in 1991, majoring in Russian Language and Linguistics & Russian Area Studies, and receiving honors for his thesis, “Swearwords and Prayers: Contemporary Russian Rock Poetry.” He completed his Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University in 1998, writing his dissertation on Viacheslav Ivanov. After teaching for three years at Dickinson College, in 2001 he was hired by the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Chicago. He also became a member of the Department of Cinema and Media Studies and the College, and was an associate member of the Divinity School. He served as chair of the Slavic Department, Cinema and Media Studies, and of the Fundamentals program. He published an astonishing amount of work across an extraordinary range of topics and approaches. His first book, The Russian Prospero: The creative universe of Viacheslav Ivanov, was followed by two books on Tarkovsky, including Andrei Tarkovsky: Elements of Cinema, which has been translated into Chinese, Farsi, and Portuguese, and will be published this year in Moscow in his own translation into Russian (Тарковский: Стихии кино). Over the next several years he produced a critical biography of Dostoevsky, a volume of translated and annotated essays by Ivanov, and an anthology of Slavophile literature. He edited numerous volumes and journal issues in both Russian and English, and became a trusted authority in matters of translation, including most recently in a beautiful dual-language volume on Eisenstein’s home. Just days before his death he completed work toward a volume of his collected essays in Russian, which will be published in Russia in the series Sovremennaia Rusistika. He was also completing a highly anticipated book, Soul Machine: How Soviet Film Modeled Socialism, which represents tremendous labor over many years.

His breadth of interests and approaches is attested by the range of topics of his articles: from Russian iconography, to Martin Heidegger and Russian Symbolist Philosophy, to the Soviet obsession with peat. He was a scholar of the old school in terms of his philological rigor and philosophical depth, but he was at the same time deeply engaged in new models of scholarship, and was noted for his political engagement and concern for issues of gender and racial equality. He had recently been working more in the intersection of art, exhibition and scholarship, in the hope of reaching new audiences through new forms. Characteristic of these later tendencies are his publications in e-flux (“Articulations of (Socialist) Realism: Lukács, Platonov, Shklovskii,” “How to Keep Communism Aloft”), The Point (“1989”), and Portable Gray (“Moscow Diary”).

He also worked on himself, even in his illness—from his early resolve to make best of the situation and his commitment to fight for time, to his stoic reports on the relentless progression of the disease, even as his condition became increasingly grave. He contributed two beautiful essays on his illness, both exemplifying his pristine prose and measured reflection: “Illness in a plague year” (The Point, April 15), and “The Omens: Tarkovsky, Sacrifice, Cancer,” which just appeared today, September 9, in Apparatus. He did not succumb to bitterness, but spoke of plans to spend time with his family, of his appreciation for his home, and of the rich variety of berries cultivated in his garden.

Eternal memory, dear Robert. You left so much behind for us, and will continue to be present with us in so many ways.

—William Nickell, Chair of the Slavic Department